The power of Do No Harm in design: Part one

Do No Harm is a concept often applied in healthcare, humanitarian, academic, or NGO worlds. While it may seem unconventional, when Do No Harm is applied to the field of design, it has significant potential and broad utility. So, what makes it such a valuable business consideration, and how can you put it into practice?

Contact info for Dr. Pardis Shafafi

Contact info for Giulia Bazoli

This is the first instalment of our two-part series adapted from Do No Harm framework for design, an Interaction 23 session developed and presented by Pardis Shafafi, Strategic Design Lead, and Giulia Bazoli, Lead User Experience Designer, at Designit. Stay tuned for part two, coming soon.

Design is the process by which the politics of one world become the constraints of another. In other words, design is an act of power. As a designer, you craft products, services, and systems that impact everyone. So how can you be more aware of your bias, privilege, and responsibility to the systems you design for?

While design does a lot of good, it’s important to think about its consequences. Political polarisation, echo chambers, addiction to our phones and social media, anxiety and isolation, and misinformation are just a few of the many problems that the design discipline has created or was part of creating. And today, with the ever-growing challenges of the modern world, the layers of complexity are multiplying.

Let’s consider two examples. The Apple AirTag has been positioned as a useful helper in finding lost luggage in overwhelmed airports. But it has also had unintended consequences, such as helping facilitate control of a partner’s movements without their knowledge – a common scenario in abusive relationships. In the context of the Iranian revolution, face-recognition algorithms have been used by the Iranian government to identify women who don’t follow the hijab laws which has led to arrest, torture, and executions. Of course, there are many other products and services which are yet to create harm but follow similar trends in their potential for unintended use and harmful consequences.

At this point, you might be thinking that by selecting only the worst actors and consequences, the current landscape is of course going to sound tragic. And while that may be true, even actors with good intentions to improve society and support people should undergo the same level of scrutiny as those who have bad intentions from the start.

Take Thinx, for example. Thinx is a brand which has long marketed itself as a safer and more sustainable option to menstrual hygiene. Recently, its products were found to contain toxic chemicals, putting it at the centre of a class-action lawsuit. While the product likely started with good intentions, its use has led to unintended negative consequences.

When something is current, it creates currency. We praise the growing support for initiatives like diversity and inclusion and sustainability, and with their rise in popularity, they too have become a currency. Currency has the potential to expand the realm of actors that will play in this space without investing in Do No Harm from the start.

How can Do No Harm contribute to the design space?

The concept of Do No Harm comes from the Hippocratic Oath, which is the vow of ethical practice historically taken by healthcare physicians. The oath says,

“The physician must be able to tell the antecedents, know the present, and foretell the future — must mediate these things, and have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm.”

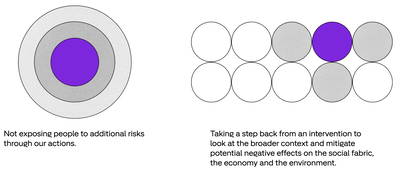

The language is a translation from old Greek that can be broken down into two main directives: First, not exposing people to additional risks through your actions, and second, taking a step back from an intervention to look at the broader context and mitigate potential negative effects. In the context of design, that typically means consideration for the individual, society, economy, and environment. There are also different types of harm to consider in this framework, which can include physical, psychological, environmental, and societal, to name a few.

Time is an essential element, too. You can think of it like an axis with immediate harm on one end (either at the time or immediately after something has taken place), and longer-term harm, which can happen long after your intervention has ended, e.g., years after a product has been designed and launched.

In practice, these elements come together to call for a twofold response: Identifying risks that could happen in a specific situation and then coming up with appropriate measures to counterbalance them.

To give an example, my colleague Giulia and I worked on a research project on undocumented women and their healthcare needs in Oslo, Norway. Ordinarily, we would go straight to the direct users of the existing service to unpack their needs. But in this case, contacting this subset of women would make them more visible, putting them at risk of deportation by Norwegian authorities. From the outset, we applied a Do No Harm lens that helped determine our next set of actions.

Since we knew the key healthcare needs of this demographic had already been extensively researched, we decided to base our initial discovery on existing findings and compare it with expert interviews from outreach workers, allowing us to accomplish our goal while mitigating the risk to the people we were designing for. This probably sounds very basic – and it should. Do No Harm often shares many qualities with good, ethical research practices.

Do No Harm is about engaging with a situation actively and intentionally. It does not mean ‘do nothing’. If the design discipline is to evolve into a safer and more conscientious version of itself, we need to develop approaches from within to be able to effectively forecast, prevent, and respond to harm. A disciplinary culture shift is in order, and the Do No Harm framework provides a way towards achieving it.

What is the Do No Harm framework for design, and how can you put it into practice? Learn more in part two.