The simple path to insights

Many problem solvers — design researchers, consultants – especially early in their careers, find it hard to generate insights reliably. It’s not that they don’t know how to do it: they have seen and created insights before. The fear can sometimes be of being unable to get to insights reliably.

Contact info for Jonathan Kahan

Strategic Design Director,

Madrid

This is because practitioners tend to think of insights as sudden realisations that happen magically when you think really hard about a problem.

This is not the case: there are reliable ways to generate insights. Let’s look at how you can easily picture where the insights sit when you think about a problem in spatial dimensions. Armed with this as a tool, a problem solver can confidently approach any situation and create value.

What are insights?

But before we dive in: what is an insight?

An insight is an “aha!” moment. It often occurs when you suddenly view a problem from a new perspective, allowing you to make connections or identify previously unnoticed patterns.

Simply put, an insight is something interesting.

Every problem has a knowledge baseline, what is known at the start. There are also often preconceived ideas on how new knowledge can be created or where the solution space will be the so-called common sense. So, something interesting either extends your knowledge baseline or challenges common sense. If you’re a consultant, a good insight is 80% of what you get paid for.

The problem-solving cube

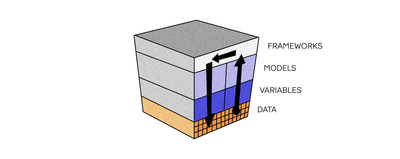

Let’s visualise the problem as a cube. On the vertical dimensions, you see the core elements of problem-solving: the frameworks, models, variables, and data.

- Models are at the core of problem-solving. A model is a simplified representation of an observed or imagined reality driven by a goal — in this case, solving the problem at hand. Any model comprises an abstract, a-priori part — the framework, and an empirical part, data, organised into variables.

- Frameworks, also known as mental models, result from your previously accrued knowledge about the world. They are generic templates that help you think about a class of problems — e.g., breakdowns, curves, and matrixes. Examples include the BCG matrix, the normal distribution curve, and the Service Design blueprint.

- Variables represent selected elements of reality in your model. In the BCG matrix case, the variables are market growth and relative market share.

- Data, which in this context can be quantitative or qualitative, is the closest part of the cube to the actual, physical world. They’re the values your variables take in the specific instance under observation.

To clarify with an example, you can model a target population using the framework of personas. The variables required include demographics, behaviours, and more, and the data you plug in will result from your actual observation of real-world people. This whole ensemble constitutes a model of that particular population.

The core of problem-solving is the iterative loop of applying frameworks to data and reinterpreting frameworks with new data. You can visualise your work as a problem solver by using a framework for a problem, collecting the data necessary to validate or falsify it, adjusting the framework to the new evidence, and so on until you converge on a model that is both accurate enough and novel enough to generate a good solution.

It goes without saying that developing insights is a core part of this process.

On the z-axis of the cube, you have a simple representation of domains. Your core domain, loosely defined, is the area, vertical, sector or subject within which you’re operating. For example, in developing solutions to help a bank retain its clients, you can define your domain as financial services, digital products for financial services or loyalty-enhancing solutions.

You can imagine this side of the cube to be infinite. All possible knowledge lies on some continuum, and your skills as a creative problem solver are largely based on your ability to move seamlessly on this spectrum.

So now that you’ve visualised the problem-solving space let’s see how you can develop insights.

The three steps to insight

To generate these captivating insights, you can follow a three-step process:

Preparatory step: understanding the knowledge baseline

The first step towards generating valuable insights is to thoroughly assess a project's existing knowledge. This involves identifying assumptions, uncovering hidden biases, and understanding the relationships between various data points. For example, when researching a new product, you have to evaluate the target audience’s preferences, industry trends, and competitors’ offerings. This initial assessment forms the foundation upon which you can build your insights and uncover areas for innovation.

Importantly, for consultants, this means clearly understanding what your client knows. In most cases, you won’t be able to accumulate the knowledge your client has built up over the years in the timespan of a project. That’s fine and expected. But it’s essential to understand:

- What is the client’s known and unknown unknowns? Known unknowns are typically the ones they pay you for; real value, though, often lies in uncovering unknown unknowns. The best way to do this is by reframing the problem statement — you can read more about that here.

- What is project common sense — where does the client expect that solutions will come from? Delivering a good solution will often involve challenging such common sense — but not so much as to cause outright rejection.

Getting to insights — approach 1: diving into the data

Step 2: Analysis

With a comprehensive understanding of the baseline knowledge, you can delve deeper into the data through three primary avenues:

1. Exploring data: zooming in

This is the most obvious approach, but it’s important. It involves collecting new information or examining existing datasets more closely. For example, a company looking to improve customer satisfaction might conduct surveys and interviews to gather additional feedback or analyse existing customer support logs to identify recurring issues. Consultants will routinely start a project by ‘crunching some data’ in their dataset or doing exploratory data analysis. The type of things you’ll be looking for will change from project to project, but some of the key questions to ask could be:

- What are the average values in your dataset?

- How widely spread is your data?

- Why are there outliers? What do edge cases have in common?

- What are the trends in a time series? What do they depend on?

- Is there any sign of Simpson’s paradox?

In the cubic project space, you’re looking at a vertical downward movement: unpacking data to uncover insights.

Getting to insights — approach 2: using different frameworks

2. Applying different frameworks: Moving up and down

A potential game changer is viewing data through different lenses, like taxonomies, explanatory models, or predictive tools, which can help you gain fresh insights. In the context of the retail project, a taxonomy could be used to categorise customer complaints by type; an explanatory model might illustrate the relationship between staff performance and customer satisfaction, and a predictive tool could forecast the impact of proposed solutions on future customer satisfaction levels. In a manufacturing setting, a consultant might apply a ‘lean manufacturing’ framework to identify areas of waste and inefficiency; they could also think of eliminating waste completely through circular manufacturing.

Here the key is challenging the project’s common sense by applying unexpected frameworks.

In the cube, you’re looking at a vertical up-and-down movement: you have a dataset, which is, by default, sliced according to an existing framework. You move up two levels and ask yourself which other frameworks could make sense of your data.

Naturally, to facilitate this step, it helps to know a lot of frameworks. This can be learned in time, but there are cheats. Check out this collection of 500+ frameworks as an example.

Getting to insights — approach 3: finding similarities with different domains.

3. Drawing parallels: Moving sideways

Uncovering connections between seemingly unrelated contexts or sectors can also yield valuable insights. For example, the retail team could examine customer satisfaction strategies employed by successful companies in other industries, like hospitality or e-commerce and adapt these strategies to suit the retail environment. A healthcare provider aiming to improve patient experience could draw inspiration from the hospitality industry’s focus on customer service and adapt those principles to their context.

Here you need to tread carefully: depending on the client, you could risk confusing them. But you also have the highest innovation potential.

On the cube, you’re starting from your framework and moving sideways into extended domains of the problem.

Step 3: Insights elaboration

So, let’s say you apply your analysis methods individually. How do you know when you’re onto something? The simple answer is when you say “Aha!” (Or when you think your client might say it).

The insight has to be:

- Non-obvious

- Generalisable — besides rare exceptions, the insight needs to be telling you something beyond itself.

- Actionable — you need to be able to do something about it

So, when fleshing out an insight, you need to make sure you’re adding a ‘so what’ — why is this important, and why does it affect the project?

Here are a few additional tips on where to look for insights within the problem-solving space:

- Look for edge cases. Averages are typically well-known. Outliers and edge cases, on the other hand, are often surprising. The big question, of course, is how important they are as a signal.

- Look for contrast. Many well-known macro-trends contain counter-trends that are sometimes the result of some maverick doing things differently, but that can also be an early sign of a pendulum swing.

- Look for anecdotes. While statistical relevance is essential, even anecdotal or non-generalisable findings can offer valuable insights. For instance, an innovative solution adopted by a single company in a different industry might inspire a ground-breaking new approach in another field. The key is to remember that innovation often stems from what is not average or mainstream and that providing compelling examples to support your insights is crucial for their effectiveness.

Insights generation as a teachable skill

The ability to generate insights is a skill anyone with the right approach can cultivate. By systematically evaluating the knowledge baseline, analysing data from various perspectives, working on frameworks, and elaborating on tensions and gaps, you can unlock the innovation potential and empower individuals to contribute meaningfully to their fields. With this framework in hand, you can more confidently embark on innovation projects in the full knowledge that insights are somewhere out there, and they will come out.

Interested in learning more about the spatial approach to problem-solving? Reach out to our Strategic Design Director, [email protected].